Diversity and Inclusion in Dietetics: A Student's Perspective

- Emily Guzman

- Jun 22, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 9, 2020

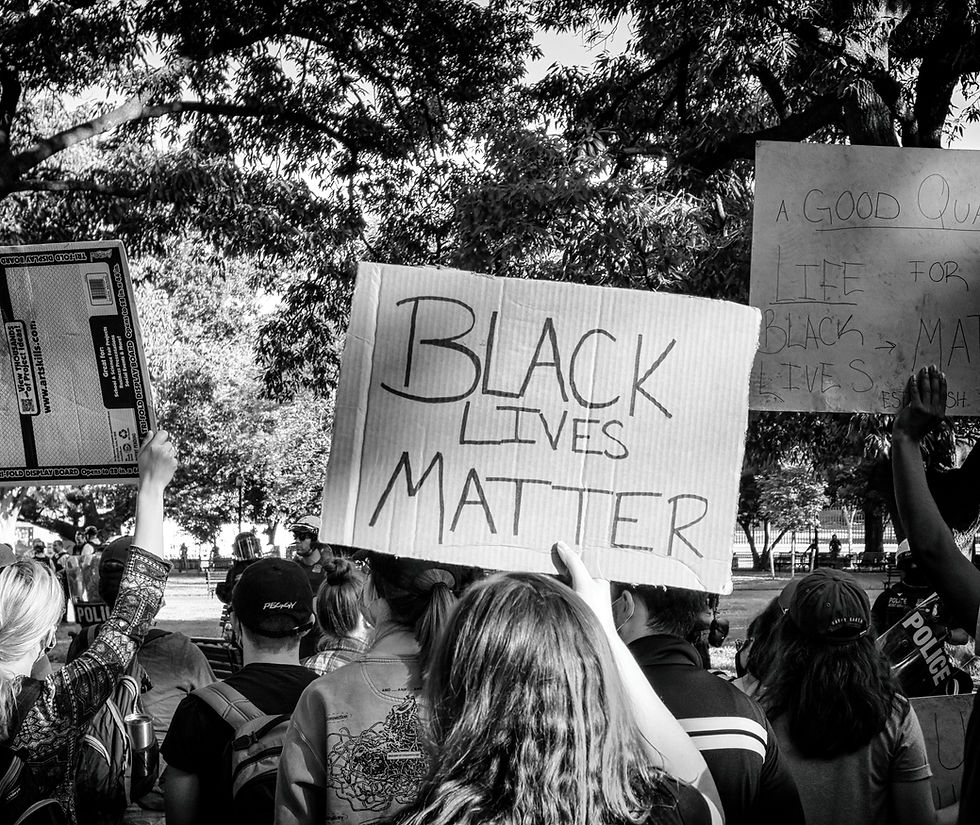

Nine days after the death of George Floyd, in response to growing calls, emails, and petitions from Registered Dietitians (RDs) across the country, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (or AND, the national agency that represents dietitians around the world) posted a statement affirming their commitment to address structural racism and promote diversity and inclusion within the overwhelmingly white and female dietetics profession.

Over 400 comments flooded the Academy’s Instagram account, where they linked to the statement and posted the following message: “To our members calling for change: We hear you. We stand with you.”

RDs were disappointed by the Academy’s delayed response, and this post instilled little confidence that meaningful change and action would follow. RD members criticized the statement’s failure to specify actions the Academy will take to ensure inclusion and diversity and to undo systemic racism in healthcare.

They demanded to know the Academy’s plans for diversifying its leadership team and amplifying the voices of black and brown dietitians. They demanded the Academy make nutrition care materials more diverse and inclusive of other cultures, address the financial barriers that make the education and training to become an RD highly inaccessible to black and brown students, and make policy changes that support its black members.

Academy leaders issued a follow-up statement that outlined specific actions they have begun taking to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion. Once again, the comments poured in from RDs lamenting the Academy's failure to address how it would make nutrition education and training more accessible and less financially burdensome to students of color.

--

According to June 2020 statistics from the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 93.9% of all RDs are women. Eighty-one percent of all RDs identify as white, 3% as Latino, 2.6% as black, and 0.3% as American Indian. In my home city of Chicago, the numbers are similar; eighty-four percent of all RDs are white, 2.5% are Latino, 2.1% are black, and 0.1% are American Indian. At the same time, population estimates in Chicago reveal that 30% of the population is Black and 29% is Latino.

All of this is to say, we don’t have nutrition professionals who reflect large populations of people in cities around the country, including Chicago.

There’s a reason students want to learn from teachers who look like them. It’s the same reason patients want providers who look like them. They understand the culture and lifestyle of the people they serve. They understand the social, cultural and environmental barriers to health. They are familiar with common foods, language, and practices. Their recommendations will be culturally relevant and sensitive. All of this translates to better relationships, better experiences within the healthcare system, and better health outcomes.

--

I’m one year into a master’s degree in nutrition and the abovementioned issues are apparent.

Even though my university is more diverse than others, my specific program still feels like a microcosm of the dietetics profession. I’m one of the few students of color and most of my professors are white. When opportunities to talk about sensitive topics present themselves, the conversation either doesn’t happen or falls flat as students choose not to engage. To be fair, our classes are so large and class time is so limited that it’s difficult to create an atmosphere of trust that allows for deeper conversations.

Several classmates and I recently debated if our program has a responsibility to teach us how systems of power and privilege impact a person’s health. Some of my peers argued no; they take it upon themselves to seek out that information because we can’t expect a program that puts undergraduates and graduates in the same classes to reach that depth.

I disagree. It may be complex and time-consuming but it’s also relevant and necessary to our profession (And if you're wondering why and how systems of power and privilege impact individual and community health outcomes -- more on that in an upcoming post.). We’re just not willing to do the work and demand more from our education. We already talk about the social determinants of health in class – things like socioeconomic status, education, physical environment, employment status, and access to healthcare. But how about we really talk about – all of it, including racism and racial disparities in healthcare.

I didn’t learn about racism as a public health issue in school. I had to read the news and listen to people’s stories to get that information. It would be hard and uncomfortable to have these conversations in class, but it’s harder and more uncomfortable for black and brown patients to receive treatment from dietitians who know little about what they’re up against.

These gaps in our education exist because of who is and who’s not in the classroom. I want to see more students and faculty of color. I want the curriculum to reflect the fact that healthcare is a social justice issue. I want my teachers to talk about queer and trans health and educate us on the physical and mental health consequences of things like racism, weight stigma, trauma, and lived experience. I want us to talk about implicit bias among healthcare providers and receive bias reduction training because it’s clearly demonstrated to have a negative impact on patient health. I want them to acknowledge the many perspectives to health and wellbeing that exist, not just the weight-centric approach that dominates our healthcare system and shapes our education. I want them to call out oppressive systems and health policies that harm and exclude marginalized people. The list goes on.

It’s my personal belief that I shouldn’t have to spend hours educating myself on issues that are by no means peripheral to health and nutrition. We have to do better for the future of the nutrition profession. Rethinking the education and training of nutrition students is a great place to start.

References:

Comments